Some of you reading will see the title and think “This is going to be interesting”. Others will see the title and think “What on earth is a microbiome?”

Let’s start with the basics. The microbiome refers to the collection of micro-organisms that travel around with you 24/7/365. What kind of micro-organisms you might ask? Well . . . bacteria, virus, molds, yeasts, parasites. And, there are a lot of them! Different interpretations have been made about the number or volume of micro-organisms that reside in or on the body and this is a bit of an academic argument – however it has been postulated by some that an average human body has about 10 trillion cells. The amazing thing is that the number of micro-organisms are greater by 10 times! Yes, 100 trillion micro-organisms living in us or on us. Furthermore, these micro-organisms have their own genes, and the total “genetic pool” of these organisms represents 99% of the genes that we carry around. That is, your own genes represent only 1% of the total genes that are looking at this article. This astounding information has led some science editorial writers to ask the question, “Who is in charge here?” Well, the answer may very well be “the bugs”. The influence that the microbiome has on health and physiology is constantly being re-evaluated – thousands of peer-reviewed articles are published every year on the relationships that exist between “good” microbiota and “good” health, as well as “bad” microbiota and “bad” health. And when I say health, I mean the health of the heart, lungs, gastro-intestinal tract, immune system, skin, and the brain – really, there are not any tissues in the body that are not affected by the collective influence of the microbiome.

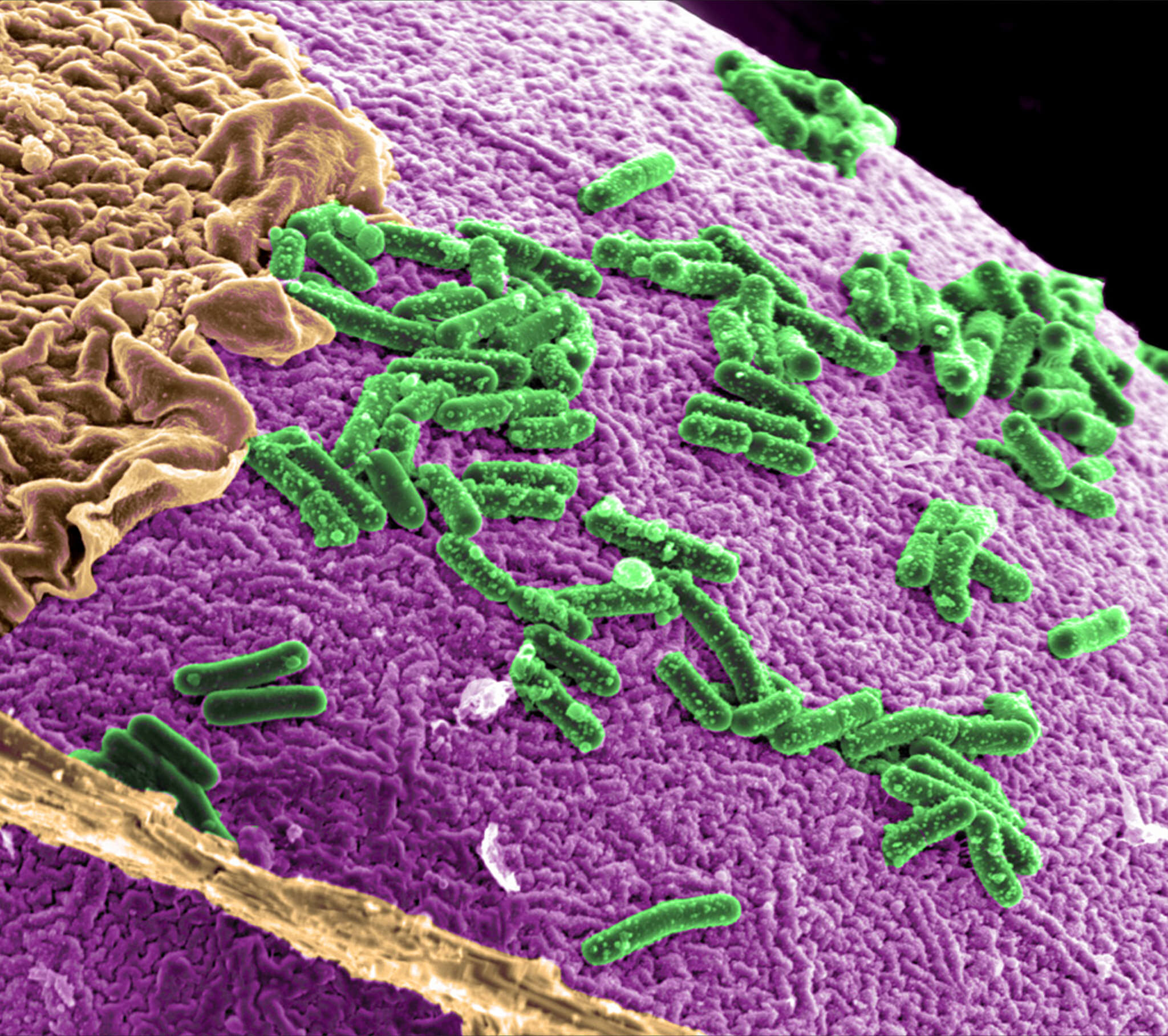

These “bugs” inhabit every square centimetre of our skin, but the bulk of the awareness of the microbiota are toward those bugs that exist in our gastro-intestinal tract. (Note: Some academics in this field refer to the bugs as being the “microbiota” and the gene pool of the bugs being the “microbiome”. This is correct from a terminology perspective, and yet most people use these terms interchangeably – you may find me going back and forth – for the purpose of this blog, both terms are being used to describe the bugs and not the genes, unless stated). The bugs in our GI tract perform all kinds of functions – from producing enzymes and vitamins, to aiding in the digestion of food, to being the “gatekeepers” of the intestinal tract, to stimulating the immune system and a host of other functions. Now, this is when the bugs that exist are “good guys”. When the bugs that we have are “bad guys” there are a host of bad things that they contribute to including inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, poor digestion, food intolerances, food allergies, autoimmune disease, skin disease, hypersensitivity reactions, and brain disease – particularly mood disorders as well as Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia. The “take-home” message is that the microbiome has a very significant influence on whether we live healthy or sick lives.

Another interesting point is that every single person on earth has a unique microbiome. The microbiome is as individual as we are. It has been determined that there are in the range of 1000 different species of bacteria that can inhabit the human GI tract, and each one of us houses 200 to 600 of these species. Even members of your own family have different microbial flora than you. The science in this field has been moving at an accelerated pace for 10-20 years and yet there is still a great deal to learn. One of the more recent findings has been in the area of what makes the microbiota function poorly and what makes it thrive. What has been known for quite a while is that the use of antibiotic medications wreaks havoc on the flora. Using antibiotics when they are truly necessary is still an important thing – in some cases, lifesaving. However, the over-utilization of these drugs is a major issue. Frustratingly, many people are unaware of the volume of antibiotic medication that is used in food production (animals) and ultimately gets into our food supply, ultimately causing issues with our microbiota. The simple message is that antibiotics are non-discriminatory – they kill the bad bugs that make us sick and they kill the good bugs that keep us healthy. With the increasing knowledge about the importance of our intestinal bugs, we are starting to seriously question the use of antibiotics in circumstances other than infectious emergencies. Other chemicals also have negative effects on the GI flora – these include the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, herbicides, pesticides, food preservatives, and the list goes on.

What can we do to preserve or improve the microbiota in our gut? Certainly the utilization of “probiotics” or good bacteria has been a strategy in place for a few decades. Recently, there has been some debate in the scientific circles about just how much benefit is derived from the consumption of probiotics. The uniqueness of our flora suggests that there should not be a “one size fits all” probiotic strategy. This being said, what, then, is the right probiotic for you? Quite honestly we don’t know. What we do know (or at least what the current consensus is) is that we need to promote diversity of the flora. This can be achieved through probiotics by ensuring that you consume as many different species of bugs as you can. Most notably, this includes the consumption of fermented foods. The other way to create diversity in your microbiome is to consume large volumes of plant material and as many different types as you can. You see, the best bugs love to eat plants – so, when we eat plants, they (the bugs) eat plants. When we eat ice cream, the bugs eat ice cream. Bottom line is this – we have the capacity to influence our own microbiome and therefore to influence our own health. The microbiome has remarkable effects on how well (or poorly) our body functions and what we put in our mouths has an enormous influence on what type of microbiome we carry around with us.